Mark Beasley on John Russell

March 2nd, 2010

British Invasion! John Russell is the Artist of the Month for February 2010, fingered by curator/selektah Mark Beasley.

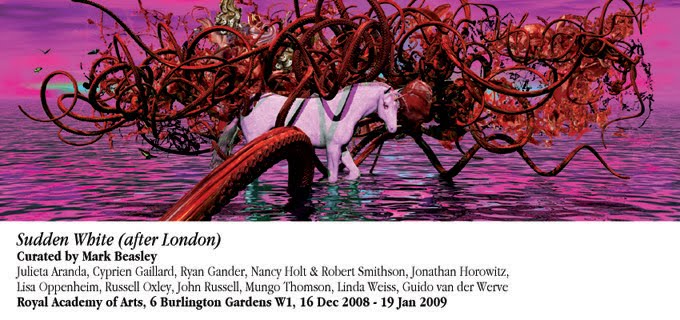

Russell was most recently praised for his digital collage murals, which The Guardian described as “stupendous cinema-scale, Pollock-wide Photoshopped phantasmagoria…the digital marriage of Peter Paul Rubens and Jeff Koons in the mind of a mad sea god.”

Russell calls his AMC print by the featherweight name Untitled (Abstraction of Labour Time/ External Recurrence/Monad).

The archival ink shimmers on metallic polyester film, and reminds me of some of the “collector’s edition” superhero comics marketed with irresistible “chromium covers.”

John Russell has exhibited work in solo and group shows for over 20 years, and has teamed up with Mark for several projects. Let’s hear from Mark about their knockin’ about…

Michael: In 2004, you worked with John at PS1 on a film and painting project titled ‘The Thinking.’ Was that the first time you worked formally with John Russell?

Mark: That was the first time that we produced a jointly authored work, with the help of cult LA film-maker Damon Packard: the resultant film ‘Lost in the Thinking,’ won mocumentary of the year at the Berkeley Film and Video Festival! I was firstly aware of John through his work with BANK, a cult of another kind. They produced a series of exhibits in London throughout the nineties that were both artwork and group show, with heady titles such as ‘Zombie Golf,’ Cocaine Orgasm’ and ‘Charge of the Light Brigade.’ BANK was a key group for many fledgling curators and artists in Britain at the time, whose story as such hasn’t been fully explored. I was drawn to the work of BANK, and particularly, John, for his irreverent, witty and theoretically savvy, but unleaden approach to art making. It appeared lively and didn’t follow any prescriptive approach, the fact that it was hard to pin down appealed to me; it seemed wonderfully at odds with the one-liner work being produced at the time. Prior to ‘The Thinking,’ John and I worked on a series of co-curated shows, such as ‘Angloponce,’ at the Trade Apartment, London and ‘AXXXPRESHUNIZM’ at Vilma Gold, also in London.

Michael: And you’ve worked with John a few more times since then: ‘Barefoot in the Head’ (2009) and ‘The Prop Makers‘ (2005), for example. This AMC print, along with the mural-scale vinyl prints he has unveiled throughout the last three years or so, adhere to lofty production values. I mean “lofty” when compared to his earlier work with BANK, which coughed up cheaply printed tabloids and posters, handdrawn cartoons, and various figures made of paper, wire, and sometimes wax. The BANK projects often looked decidedly provisional and lo-fi. How do you account for this stylistic transformation? Does it seem to you to be a departure?

Mark: On the face of it, yes, I guess it feels different. But fundamentally, it’s in tune with John’s continued interrogation of the vernacular of the day, whether it’s the Xeroxed zine of the BANK Tabloid or his 800-page anthology ‘Frozen Tears,’ which mimics a Stephen King bestseller. The AMC print allies itself with the explosion of rendered digital imaging. It also riffs on 70s psych poster art and the seventies pomp and prog rock connections with science fantasy – specifically, Tolkein, it seems. It’s an aesthetic that strikes fear into many – Roger Dean meets Dalí by way of Peter Paul Rubens – strictly for the strong of heart. It’s certainly not the Peter Saville studio of clean cut, well-behaved lines.

Michael: Yes, while looking through his digital images, I had to switch on Emerson, Lake, and Palmer’s Fanfare for the Common Man, which still gets unfairly shunned from most libraries. The BANK stuff felt more like Pavement or even SST records, though that wouldn’t be a parallel timeline. Anyway, the timing of John Russell’s digital, sci-fi pastiche is perfect, given the sensational spectacle of Avatar, the coming Tron remake, and the other epic, digital IMAX features that are imminent. Personally, the print, the vinyl murals, and Avatar all make me wince at their excesses, which more recent art and music have shaven away; but eventually that guarded skepticism can give way to the undeniable sentiment that “this stuff is really cool.” I guess by understanding that Russell’s newer imagery is profligate and over-the-top, we can then permit ourselves to really have fun with it. Of course, the images aren’t thoroughly kitsch; the crucified hands, permeable bodies, and flowing internal organs make things makes things a bit morbid – yet no worse than the maggots and armed Nazi corpses of Jake and Dinos Chapman.

Mark: ‘Fanfare for the Common Man’ is perfect; it is more a knowing banal excess than kitsch. Fantasy is key, not as a function of intuition or in opposition to reality, but rather as something suggested through knowledge, something that grows through montage, citation and digital reproduction. A fantasy let loose from closed and dusty volumes, a liberation of impossible worlds. A form of baroque, digital triumphalism, a becoming aesthetic that as yet isn’t fully understood. The potential appeals to me, rather than simply quoting the past so as to be clearly understood, it presents something of a curveball. What is good or bad taste and who decides?